Cholesterol must get the prize when it comes to nutritional controversy…and confusion.

There are a million myths and questions that swirl around this subject:

What exactly is cholesterol anyway?

What is ‘good’ and ‘bad’ cholesterol?

Does ‘good’ HDL cholesterol counterbalance the ‘bad’ LDL?

How does cholesterol affect your health?

What are the ideal cholesterol levels?

And finally…

What is the best way to control my cholesterol levels?

In this article, we will answer all of these questions and much more.

But first, let’s define what cholesterol is.

What Is Cholesterol Anyway?

A waxy, fat-like substance, cholesterol is an essential component of all animal cell membranes.

Your body needs cholesterol to maintain both the integrity and fluidity of the cell membranes’ structure.

Importantly, your body is capable of manufacturing all the cholesterol it needs.

In fact, each cell synthesizes cholesterol through a complex 37-step process. For example, a human male weighing 150 pounds (or 68 kilos) will synthesize around 1 g per day while his body will contain approximately 35 grams of cholesterol.

Because it is insoluble in water, cholesterol is transported through your bloodstream in small packages called lipoproteins. These are made of fat (lipid) on the inside and proteins on the outside.

Plasma lipoproteins are classified by their density:

- VLDL is a very low-density

- LDL is a low-density

- IDL is an intermediate density lipoprotein.

- HDL is a high-density

What Is ‘Good’ and ‘Bad’ Cholesterol?

Why do people talk about ‘good’ versus ‘bad’ cholesterol?

Elevated levels of plasma lipoproteins other than HDL (called non-HDL cholesterol) are associated with an increase of atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease.

This is particularly true of LDL cholesterol, which is nicknamed the ‘bad’ cholesterol because it is directly linked to the onset and progression of atherosclerosis.

HDL, on the other hand, has earned the name ‘good’ cholesterol because it carries cholesterol back to the liver, which then removes the cholesterol altogether from your body.

Does “good” HDL cholesterol counterbalance “bad” LDL cholesterol?

One of the many myths around cholesterol is the idea that you can counter the effects of ‘bad’ LDL by having enough ‘good’ HDL cholesterol.

A meta-analysis of 17 studies shows that dietary cholesterol increases the ratio of total to HDL-cholesterol, suggesting that a favorable rise in HDL fails to compensate for the adverse gain in total and LDL-cholesterol.

Another meta-analysis of 27 controlled metabolic studies revealed an almost linear relationship between dietary and serum cholesterol levels when the consumption of cholesterol falls within the 0-400 mg daily intake range. That means for each 1 mg/1000 kcal of dietary cholesterol, you may see a 0.1 mg/dL increase in serum cholesterol.

Furthermore, a quantitative meta-analysis of 72 metabolic ward studies showed that 100 mg/d of added dietary cholesterol will increase LDL and HDL cholesterol by 1.9 mg/dL and 0.39 mg/dL, respectively (i.e. a ratio of 5 LDL:1 HDL)!

In other words, the level of LDL in your blood rises much higher than HDL cholesterol—once again suggesting that it is difficult to counter the ‘bad’ with the ‘good’ cholesterol.

What about the ‘large fluffy’ LDL cholesterol particles?

Another myth argues that ‘large fluffy’ LDL cholesterol is preferable over the small dense variety.

This is true…and false.

The reality is that the ‘large fluffy’ LDL particle is relatively better for you—but it is still bad. Big fluffy LDL particles raise coronary heart disease risk 44 percent in women and 31 percent in men while small dense LDL raises the risk 63 percent and 44 percent in women and men respectively.

But even these lower percentages are dangerous.

Bottom line?

LDL cholesterol increases the risk of coronary heart disease. No matter what its size.

How Does High Blood Cholesterol Harm Your Health?

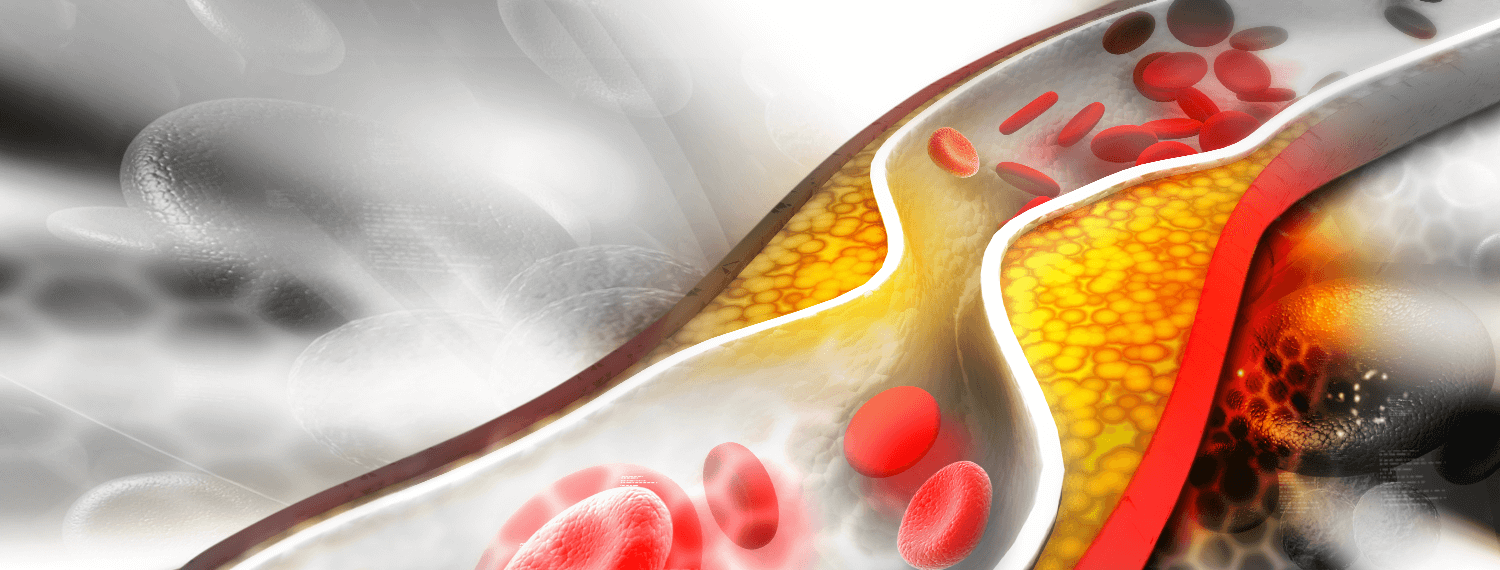

High serum LDL cholesterol promotes atherosclerosis, a condition where plaque builds up in your arteries.

Over time that plaque hardens and narrows your arteries, thus limiting the flow of blood to the heart. Eventually, plaque may rupture and cause blood clots.

If a clot blocks an artery that feeds the brain, you have a stroke.

If the clot blocks an artery that leads to the heart, it causes a heart attack.

Aside from promoting plaque build-up, high cholesterol levels may directly contribute to its rupture and the formation of clots.

Over a decade ago, researchers reported that, when examining the bodies of heart attack victims, their ruptured plaques were filled with cholesterol crystals.

Even more interestingly, they observed that no such crystals were found in the arteries of those who had severe atherosclerosis but died first of other non-cardiac causes.

The researchers then hypothesized that the cholesterol in the plaque had gotten so supersaturated that they crystallized. To test their idea, they created a supersaturated solution of cholesterol in a test tube, which expanded extremely rapidly and created crystals so sharp that they could easily cut through and tear membranes.

A bit like sugar water forms rock candy, cholesterol crystals may accumulate, ‘break’ the plaque and cause blood clots, which in turn may lead to a stroke or a heart attack.

So How Much Cholesterol Can You Eat?

In the US, the current official recommendation is to keep your total cholesterol under 200 and your LDL under 100-130. Over 240 (total) or 160 (LDL) is considered high while 200-239 (total) and 130-159 (LDL) is borderline high.

In a revealing study, researchers examined 65,000 people who were hospitalized with acute coronary conditions across 344 hospitals.

And their average cholesterol was 170 mg/dL (while their LDL cholesterol was 103 mg/dL). Well UNDER the recommended limit!

In other words, most people admitted to hospitals with acute coronary events (e.g. heart attacks) enjoy ‘normal’ cholesterol levels.

Which means our ‘normal’ cholesterol levels are likely far from ideal.

As the editor-in-chief of the American Journal of Cardiology wrote over a decade ago, “It is time to shift from decreasing risk to actually preventing and arresting atherosclerosis.”

And to effectively protect yourself against cardiovascular disease, the ideal levels seem to be between 50 and 70 mg/dL for LDL and under 150 mg/dL for total cholesterol.

Above these thresholds, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease develop.

What About the French Paradox?

One ‘defense’ for maintaining our cholesterol-rich eating habits is the so-called French paradox.

In most countries, there is a straight line when you look at the relationship between death from cardiovascular disease and the consumption of saturated fat and cholesterol.

The more animal foods the populations eat, the higher their death rates from cardiovascular disease.

However, there seemed to be two exceptions to this rule.

Finland (which did worse).

And France (which did better).

But why? How is it possible that people in France ate as much saturated fat and cholesterol as a country like Finland but had five times fewer fatal heart attacks?

Well, it turns out that, in fact, there really is no French paradox.

According to a World Health Organization investigation, French physicians under-reported cardiovascular disease deaths by as much as 20 percent. When you correct for the underreporting, the French experience seems to be similar to other countries in Europe—there is a direct relationship between the consumption of animal foods and death rates from cardiovascular disease.

What Is the Best Way to Lower Your Cholesterol?

The absolute best way to lower your cholesterol is to greatly minimize your consumption of cholesterol as well as trans fats and saturated fats.

Because while trans fats and saturated fats are bad in and of themselves, they are also dangerous because they both increase LDL cholesterol.

So you need to get the levels of all three—trans fats, saturated fats and cholesterol– as low as possible.

Very importantly, the National Academy of Science sets no tolerable upper intake level for cholesterol.

This is because any intake above zero increases LDL or ‘bad’ cholesterol.

In other words, there is no ‘safe level’ of cholesterol…which is also the case for trans fats and saturated fats.

So what does this mean when it comes to eating? What should we consume if we want to lower our cholesterol levels?

A simple rule of thumb?

You should increase your intake of fiber-rich, plant-based foods.

Fiber bulks, speeds and dilutes the intestinal waste stream, facilitating the removal of excess cholesterol from the body.

And you should decrease your consumption of cholesterol- and saturated fat-rich animal foods as much as possible.

Just by cutting down on animal foods (which have no fiber), you may lower your cholesterol 5-10 percent. If you go a step further and adopt a vegetarian diet, your cholesterol level may drop 10-15 percent. Eating vegan may get you down 15-25 percent while consuming a minimally processed, plant-based diet may decrease your cholesterol levels by 35 percent or more.

It is a continuum.

But the closer you get to a whole food, plant-based diet, the better.